On May 17, 2025, the M/V River Harmony docked in Nuremberg Germany, a city layered in centuries of history and emotion. Our group disembarked the ship by 9:30 AM and boarded the waiting buses for what would be a profound and fascinating day ashore.

|

| Grand Circle 14 day river cruise Vienna to Amsterdam itinerary |

|

| M/V River Harmony |

Our first stop was the vast and haunting Nazi Party Rally Grounds, a sprawling complex that once covered more than four square miles on the outskirts of Nuremberg. Built as a monumental stage for Hitler’s regime, these grounds were designed to convey power, discipline, and absolute control. We stood before the skeletal remains of the Zeppelin Field grandstand, where Hitler once delivered fiery speeches to crowds of up to 200,000 people—rows upon rows of spectators tightly packed into formation, flanked by towering banners and floodlights designed to create a theatrical, almost hypnotic spectacle.

|

| Zeppelin Field Grandstand 1938 Photo:Public Domain |

|

| Zeppelin Field Grandstand 1945 Photo: Public Domain |

Today, the empty terraces are cracked and overgrown in places, the stonework stained and broken, a haunting contrast to the chilling order that once reigned here. Our guide explained how every architectural element—from the grand symmetry to the sheer scale—was meant to psychologically overwhelm and impress. Walking across that open field felt surreal, like stepping directly into a black-and-white propaganda reel. It was both sobering and eerie—a concrete reminder of how spectacle was weaponized in the service of tyranny, and how quickly grandeur can become ghostly in the wake of evil’s collapse.

Zeppelin Field Grandstand 2025

Our next stop was the Palace of Justice, a large and stately building still in use today, yet forever marked by its role in a defining moment of 20th-century history.

Inside, we entered the infamous Courtroom 600, the site of the Nuremberg Trials—a groundbreaking series of military tribunals held after World War II.

|

| Sharon Sparlin in courtroom 600 |

It was in this very room, beginning on November 20, 1945, that twenty-four high-ranking Nazi officials were indicted by the Allied powers—the United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and France—for crimes including war crimes, crimes against humanity, and crimes against peace. Among those on trial were some of the most powerful figures of the Third Reich: Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe; Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s former deputy; and Joachim von Ribbentrop, Nazi Germany’s foreign minister. The proceedings in Courtroom 600 of the Nuremberg Palace of Justice marked the first time in history that an international tribunal was convened to hold a government’s leaders personally accountable for atrocities committed under the guise of state authority.

|

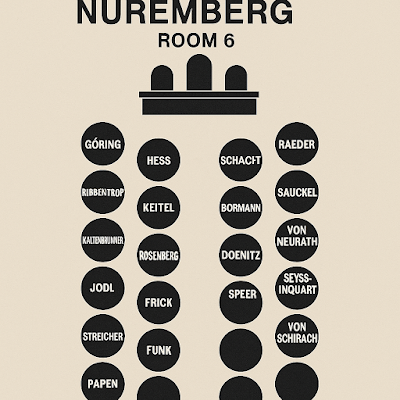

| Courtroom Seating |

Of the original 24 defendants, 21 stood trial (one committed suicide before proceedings began, and two were deemed medically unfit). The trial lasted nearly a year, with witness testimony, film footage from concentration camps, and a massive volume of documentation presented as evidence—unprecedented at the time.

The final verdicts were announced on October 1, 1946. Twelve men were sentenced to death, including Göring (who famously took his own life by cyanide capsule the night before his scheduled execution), Ribbentrop, and Wilhelm Keitel, head of the German armed forces. Three were acquitted, and the rest received varying prison terms—from 10 years to life.

What struck me most about Room 600 was how ordinary it looked—wood-paneled walls, a row of high-backed chairs, a slightly raised judge's bench. Yet the legal foundations for international human rights law were laid here. It was the first time in history that an international court held individuals—not just nations—accountable for atrocities on such a scale.

Upstairs on the third floor, the Nuremberg Trials Memorial Exhibition offers a deeper historical context to the landmark proceedings. Although time did not permit a visit, the exhibit is known for its powerful presentation—featuring audio-visual stations, interactive displays, and original trial footage that bring the courtroom events vividly to life. It also includes the “Cube 600” temporary exhibits and in-depth documentation on both the main Nuremberg Trials and the subsequent proceedings that followed. A glass case displays the trial transcripts, while another station highlights the role of each of the four Allied prosecuting nations: the United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and France. The exhibition is both chilling and inspiring—a powerful reminder that justice, though sometimes delayed, can still be pursued in the aftermath of unimaginable atrocities.

Leaving the Palace of Justice behind, our bus took us to Nuremberg’s medieval Old Town, where we were dropped off near the Schöner Brunnen—the “Beautiful Fountain.” This ornate 14th-century structure looks more like a Gothic spire than a fountain, with its intricate statues representing the seven liberal arts, the four Evangelists, and key figures of the Holy Roman Empire. Legend has it that turning the golden ring embedded in its wrought-iron gate brings good luck.

|

| Photo: Public Domain |

From there, it was a short walk to Heilig-Geist-Spital (Holy Spirit Hospital), one of the most photographed spots in Nuremberg. Built in the 14th century to care for the sick and elderly, the building arches gracefully over the Pegnitz River. Today, it houses a charming restaurant where I sat down for a true Franconian lunch: six original Nuremberg bratwursts—small, smoky, and grilled to perfection—served with tangy spiced mustard, a crisp salad, potato salad, fresh bread, and two glasses of golden local beer. Dessert was a scoop of vanilla ice cream, simple and satisfying.

|

| Entering the restaurant |

With a full belly and happy heart, I continued exploring the heart of the Old Town on my own. I wandered over to St. Sebaldus Church (Sebalduskirche), one of Nuremberg’s most historically significant landmarks. It stands as a solemn tribute to the city’s medieval heritage. Built between 1225 and 1273, this Romanesque-Gothic church is dedicated to Saint Sebaldus, the patron saint of Nuremberg, whose bronze tomb by Peter Vischer the Elder is a masterpiece of German Renaissance sculpture. The church’s façade and entrance are striking, especially the modern bronze doors and tympanum installed in the 1970s, designed by sculptor Willy Jakob. Above the doorway, a dramatic sculptural panel depicts a modern, abstract interpretation of the Crucifixion. The downward-hanging figure of Christ is rendered in a stark, angular style, surrounded by vertical elements that suggest a symbolic skyline or a forest of crosses. A sharply extended shape—possibly representing the spear of Longinus—emphasizes Christ’s suffering. This contemporary artwork, set against the church’s ancient stonework, reflects both a post-war artistic revival and a bold visual reminder of faith, sacrifice, and renewal. Inside, the lofty nave, stunning stained glass, and detailed stonework reflect the artistic and spiritual devotion that has filled this space for centuries. Despite wartime damage, St. Sebaldus Church was lovingly restored and remains a deeply moving place to visit—both a place of worship and a powerful symbol of Nuremberg’s enduring history.

Next was Frauenkirche—Our Lady’s Church—which anchors the eastern side of the main market square. Built by Emperor Charles IV in the 14th century, its highlight is the Männleinlaufen, a charming mechanical clock that springs to life at noon. Right on cue, the bell rang and little figures paraded around the Holy Roman Emperor, reenacting the Golden Bull of 1356. It was whimsical and historical all at once—such a quintessentially European blend.

Before heading back to the bus, I stopped in at a local bakery and picked up some original Nuremberg gingerbread (Lebkuchen)—soft, spiced, and coated in a delicate glaze.

I also passed the Old Town Hall, a striking Renaissance building that once housed both city government and courts. Its vaulted ceilings and grand facade reflect the wealth and influence Nuremberg once held as a center of trade and craftsmanship in the Holy Roman Empire.

|

| Local street color |

By 3:00 PM, the group was back on the bus and returning to the ship. As we drove out of the city, I found myself quietly reflecting on the contrasts I’d seen: the echo of goose-stepping soldiers and the enduring voice of justice in Courtroom 600, the medieval charm of Old Town, and the joyful chime of a mechanical clock. Nuremberg had shown me both its scars and its soul—and I was grateful for every moment.

#River Cruise 2025#Germany#Nuremburg Trials

No comments:

Post a Comment